Story by Sarah Francis

It’s 8:17 am, and it’s time to go to work. You bundle up in your Midwest-winter attire, complete with two pairs of long underwear, a heavy parka, and a face mask. You shuffle outside to warm up the car, and a rush of cold air nearly knocks you off your feet. The first thing you notice is the cold air in your lungs: your body struggles to warm it up, and you feel out of breath. The next thing you notice is a burning sensation on the tip of your nose, the only part of your body exposed to the bitter cold. After a few seconds, you feel that the hairs inside your nostrils have frozen. You look at the thermometer over your shoulder: it reads -43°F.

This bitter cold is caused by a disruption of the polar vortex: an atmospheric phenomenon where the jet stream shifts, pulling a mass of arctic air down into the Midwestern (and sometimes Eastern) United States. -43°F is very cold. To put this in perspective, the average temperature at the North Pole in the dead of winter is somewhere around -20°F. At the McMurdo research station in Antarctica, winter temperatures fall to around -18°F. -43°F is a good 20 degrees colder. Even your double-long underwear and winter parka are barely enough for this cold.

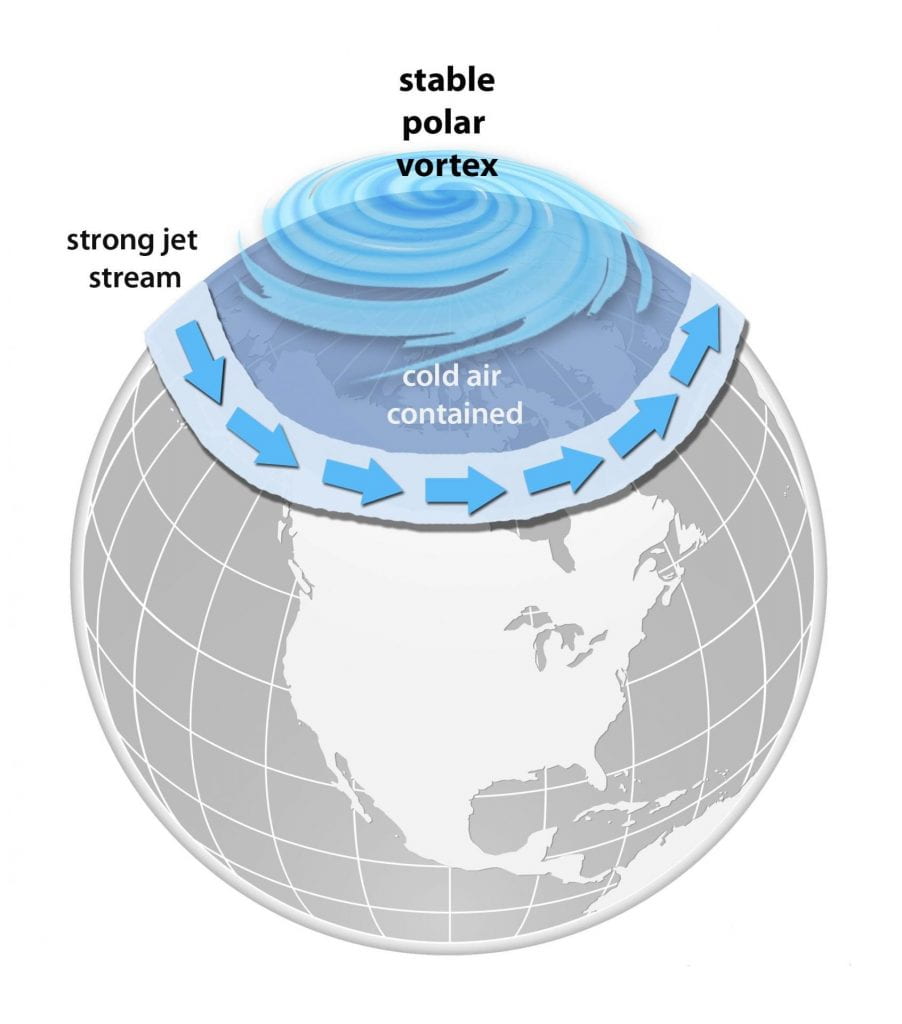

To me, the term “polar vortex” makes it sound like the Midwest was being consumed into a frigid, swirling, vortex of doom. But the polar vortex is actually a very normal part of the way our atmosphere functions; it just refers to the cold, low-pressure clump of air that hangs out north of 60 degrees latitude (the approximate latitude of Anchorage, Alaska), and spins with the rotation of the Earth (spinning = “vortex”).

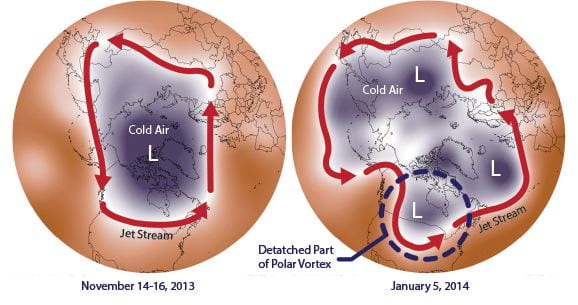

The “jet stream” is a river of high winds that occurs where this cold arctic air collides with the warmer, mid-latitude air. The jet stream shifts naturally; this is due to the chaotic nature of air swirling around in our atmosphere. The polar vortex tends to be strong in the winter, which means that its rotation is fast, and its location (and thus the location of the jet stream) remains pretty constant. Think of it like a spinning top: when it spins fast, it stays upright and stationary, but a slow-spinning top gets all wibbly-wobbly and moves all over the place. Any sort of uneven warming, or storm event, can cause the jet stream to snake around in the upper-atmosphere. A wibbly-wobbly jet stream in the wintertime can cause the arctic polar vortex to be pulled southwards, bringing apocalyptic cold to the Midwestern United States. (Images from NOAA)

This disruption of the polar vortex is a natural process, but the patterns of how often and when it will happen are still not well-understood. This year, the polar vortex disruption was caused by unusual warming (known as “Sudden Stratospheric Warming”) in Siberia in early January. Some scientists have shown that a warming arctic climate may result in more polar vortex disruptions, paradoxically bringing more unusually cold weather despite overall warming temperatures. However, climate science takes time. Since “climate” is defined as weather patterns averaged over thirty years or more, it takes several decades of information for us to be able to observe changes in climate. Because of this, many others argue that we do not yet have conclusive evidence that climate change is resulting in more polar vortex disruptions.

We do know that during this extreme cold, it’s best to bundle up and stay inside as much as possible. Only five minutes of exposure can result in frostbite, and the most recent polar vortex disruption resulted in school closures, cancelled flights, and left hundreds of homeless folks particularly vulnerable. Several people lost their lives in this record-setting cold.

(Image from ABC News)

But, the good news is, in typical Midwest-nice fashion, some community members really looked out for each other. One woman took it upon herself to rent hotel rooms for people who were stuck out on the street. Thanks to social media, she received enough donations to more than triple the rooms she could provide. Hopefully, the next time the polar vortex arrives in the Midwest, we will be ready, and we will continue to support our community through the bitter cold.