Opinion piece by Jonathan Flynn

Nobody ever said it would be easy to become a scientist. I was well aware of that as I stumbled through high school chemistry, silently vowing myself to a fate that yes, while I told myself I inherently sucked at the subject, I believed my drive to become a doctor would help me jump that hurdle.

I won’t pretend that I struggled in the same way many of my peers had. Both of my parents are college educated. My father has been a doctor for twenty-five years, and because the Navy paid for medical school, my mother was able to raise brother and me at home while he worked. As a result, when I entered college, getting help when I was upset, frustrated or overwhelmed was only a phone call away.

Yet here I am, six years later, in my last year at Western Washington University completing a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Science. I’m not going to be a doctor anymore. Instead, I’m going to become a public school science teacher. I just couldn’t take the stress or the toxicity of the pre-medicine lifestyle, and if I couldn’t do it — a straight white male with an incredibly supportive and financially stable family — then how could someone who did not have that privileged upbringing succeed?

These past six years have been exhausting. For a long time, I was living under the impression that the only way I could help others was by becoming a doctor, which meant up to twelve years (including college, medical school and residency) of long, tedious nights in the library, enduring stress-induced stomach ulcers, and the occasional panic attack.

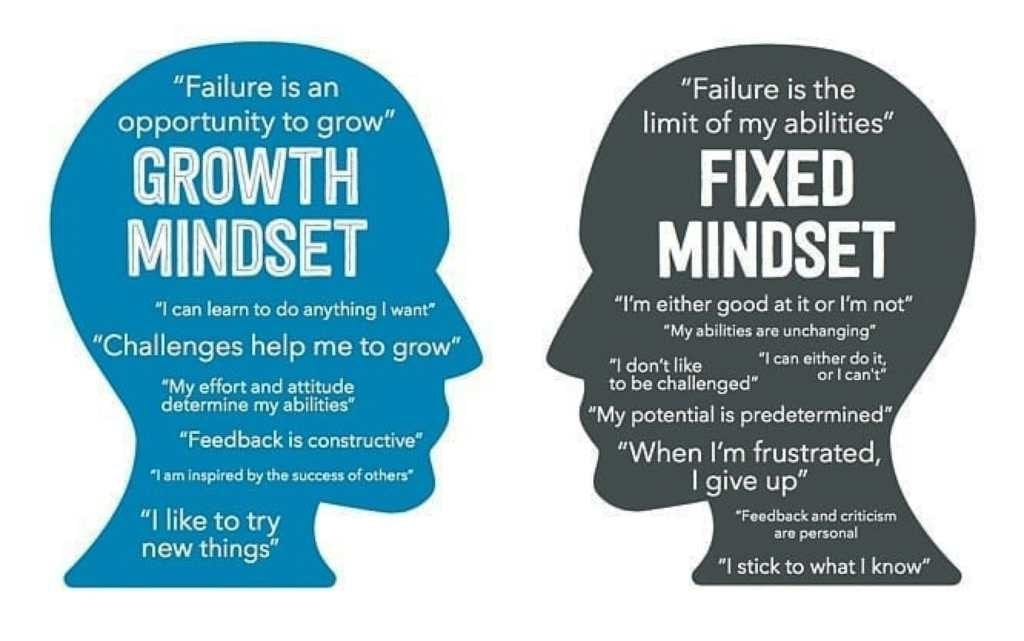

Looking back, the self-doubt and bad case of imposter syndrome I felt was very destructive, and after two visits to the counseling center at the university, I didn’t feel any better. And while my friends became the comforting support network that encouraged me to keep going even at my lowest points, I can’t say that I received the same support from my fellow students and the scientists who were tasked with teaching me. In fact, the atmosphere in my introductory science courses was quite the opposite. I following phrase was pervasive in every classroom and every laboratory:

“Either you can do it or you can pick another major.”

It’s a phrase that undermines everything science stands for. After all, weren’t we told that if at first you don’t succeed, try again? That science is all about learning from your mistakes?

Despite that philosophy, teachers and administrators continue to deliver a torrent of assignments, exams, and hours of redundant homework that cascaded into our childhoods every week. All of this in the hope that progress can be quantified. And what do we have to show for it? Well, in 2015, the Programme for International Student Assessment found that the U.S ranks 38th out of 71 countries in math and 24th in science. The numbers show it – the system we have just isn’t working.

The Programme for International Student Assessment’s results. (Source: OECD)

For those with a strong support network, with parents and friends who are there for them, that system is merely a series of hoops that one must jump through in order to become qualified for a professional career. But for others – namely our underserved communities – that system is a seemingly insurmountable mountain. For someone who received a C in high school physics, do we discount them as someone who “just isn’t a math person”, or do we recognize that the system just isn’t built for them? That these students have been fighting an uphill battle with a pack full of damaging assumptions and destructive beliefs that have been impressed upon them since they entered kindergarten (if they were able to go)?

But the fact is that even with that support network, I had a very difficult time. I did not feel welcome. I did not feel comfortable forming study groups with peers who were socialized to see me as competition for a place in medical school. Even then, I helped perpetuate that feeling. Whenever I compared test scores with a peer and found that I scored a few points higher, I silently congratulated myself for moving up in the ranks, however small that gain was.

This isn’t meant to be a scathing expose on the culture of the pre-medicine track. The path to medical school is inherently difficult and I commend those who decide to stick with it. However, we do very little to help those travelling that path. We demand they dedicate what little free time they have to studying and productivity. We make them fret over the smallest mistakes even when they succeed, and when they fail, we do little to encourage them to get back on their feet. Many of my friends have had their professors tell them to drop a class simply for receiving a bad grade, and that they’re just not a “science person” or “math person” (a myth that has been disproven time and time again).

There’s no such thing as a “math person” or “science person”. (Photo credit: Women on the Fence)

We need to change how we teach science. In fact, it’s already happening. Inquiry-based learning, the method of learning by in-class, hands-on activities, is gaining traction in progressive STEM programs nationwide. But more needs to be done. We need to change this toxic culture for those students who, in spite of the negativity and cutthroat environment we’ve established in secondary and collegiate STEM programs, decide to pursue the noble goal of becoming a doctor, researcher, engineer or professor. We especially need to reach out to those who have been forced to navigate this seemingly hostile environment without any aid because of their various identities. After all, we are the scientific community. Let’s learn from our mistakes.

March for Science, Bellingham WA 2017.