Story by Sarah Francis

“What got you interested in geology?” is a common question that people ask me on a daily basis. I usually respond that I love learning about large-scale processes such as mountain-building, and how oceans grow and shrink over millions of years, but it is also because I love studying and learning in the outdoors. The study of geology is rooted in outdoor exploration, making the field very attractive to some students, but unfortunately makes it quite alienating to others.

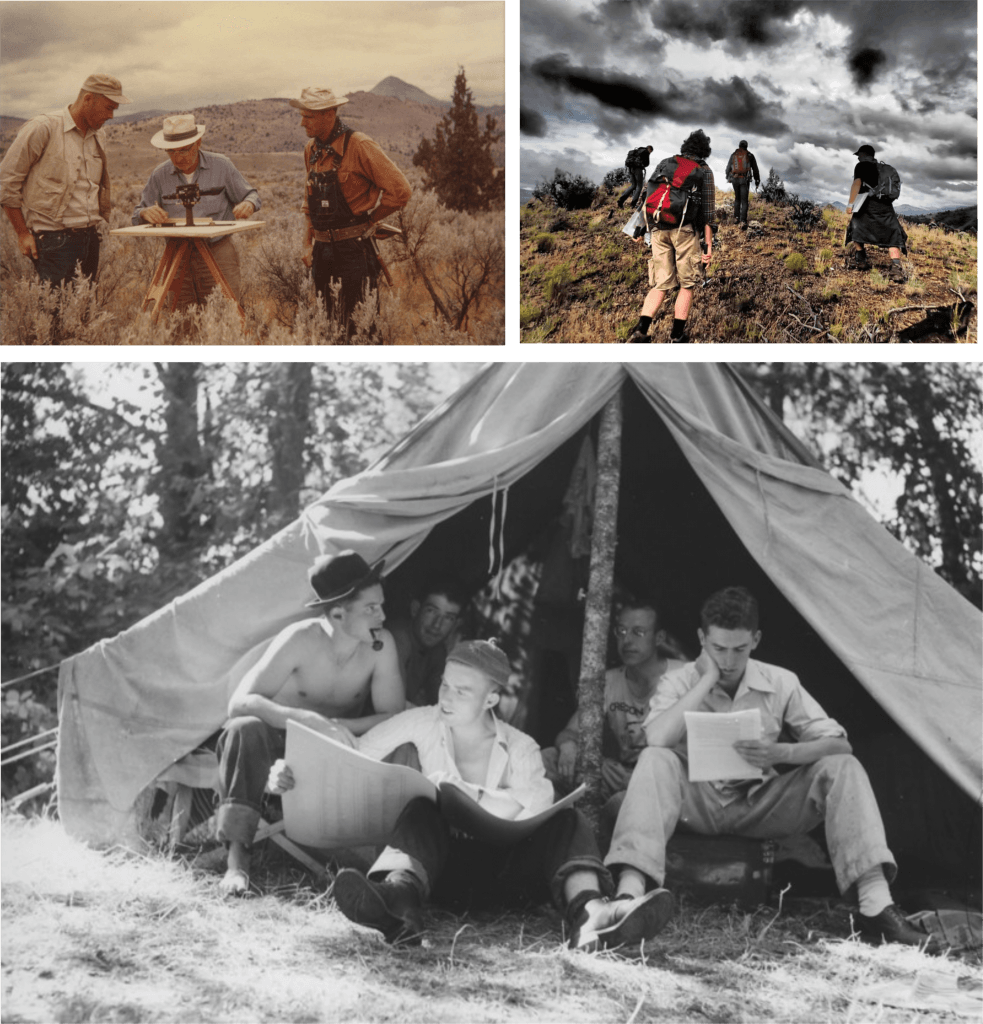

Historic photos of Oregon State geologists doing field studies in 1958, 2013, and 1938, respectively.

Many studies have shown that increased diversity in problem-solving groups results in more creative innovation and greater productivity. Unfortunately, the geosciences have the lowest racial and ethnic diversity in all of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields at all levels of higher education. According to a 2011 study, “Between 2000 and 2008, underrepresented minorities (Hispanic, black, and and American Indian/Native Alaskan students) earned 16%–17% of STEM degrees and only 5%–7% of geoscience degrees.”

Dr. Jackie Caplan-Auerbach is a geophysicist at Western and has spent a great deal of time in both physics and geology departments throughout her career.

Dr. Caplan-Auerbach enjoying the view near the ocean entry on Kilauea volcano, 2000.

“Geology is not very diverse, in part because we advertise it as an REI catalog. We aim for a specific community,” Caplan-Auerbach said.

From my own observations as well as observations of my peers, that specific community is (primarily) composed of white men who like to go camping, like the folks in the photos above. For anybody who falls outside of that category, getting into geology can be a challenging, and often unsafe, endeavor.

Dr. Robyn Dahl is a paleontologist at Western and has had her own challenges to deal with throughout her career and education.

“I do a lot of field work in very conservative, rural areas of Utah and Nevada, and my visibility as a queer woman of color requires me to always consider my personal safety,” Dahl said. “I have often brought other women and students of color into the field as field assistants, and it is immediately clear when we are welcome and we are not. We usually are very welcomed, but there have been some incidents that prove we aren’t, so I always pay attention.”

Most students who hope to earn a Bachelors of Science in geology are required to take Field Camp, an intensive field-based course where students go camping and learn to make geologic maps for up to six weeks straight.

“[Field camp] is a burden for a lot of students, financially, and it’s exclusive too, it’s not very inclusive because if you’re differently abled, etc., there’s a lot of different issues that go into that” Dahl said. “I’ve talked to students who had really bad field camp experiences, non-white students, for a lot of different reasons, mainly being less experience outdoors, were made to feel unwelcome. And that’s not cool.”

With the rise of the #metoo movement, safety for women during field studies has been particularly present in the media. Unfortunately, stories of sexual harassment and assault, often targeted at women, are far too common in these settings. “You’re not going to succeed if you’re not safe and happy,” Dahl said. For this reason (among others), far too many women end up leaving science. “We’re not really having trouble recruiting women into geosciences now, but there is a retention issue, for so many reasons,” Dahl said. This retention issue is true for women and all other combinations of underrepresented minorities in the geosciences.

Although many people face challenges in the geosciences, we are working hard to change things. Dr. Caplan-Auerbach notes that, “At the very least, we as a community are recognizing, not recognized, but we are getting there, to have more equity among our faculty, to have opportunities for people to see that anybody can be successful in this field.”

One tangible way we can begin to improve equity in geology is to address the problem with field camp. Here at Western, several faculty are working on creating an alternative field camp course that will be more accessible to all kinds of students. Dahl is one of them.

“We’re hoping that this camp will help address these larger issues of diversity and inclusion in geoscience, and we hope that it attracts students from Western and other institutions. We envision it as more a “lab camp” than a traditional field camp” Dahl said. “Modern geoscience requires a broad range of skills that don’t necessarily include traditional field mapping, so a lab camp could be fully accessible to students of all abilities and teach skills that don’t require roughing it in the wilderness all summer. We hope that this program would help nontraditional geoscience students build skills and find their place within the large geoscience community.”

It’s a bit ironic that the very thing that attracted me and many others to the field of geology is (at least partially) responsible for perpetuating the problem of diversity in geology. I love that I have been able to do some incredible field work as part of my geology degree, but I also understand that this should not be a foundation and requirement for the study of geology. Addressing the field camp problem is not the only solution, but it is a tangible step that we can take to make geology more accessible to all kinds of people. Hopefully, we will continue to find more ways to improve equity in geology, ultimately resulting in new ground-breaking discoveries within the study of the Earth.